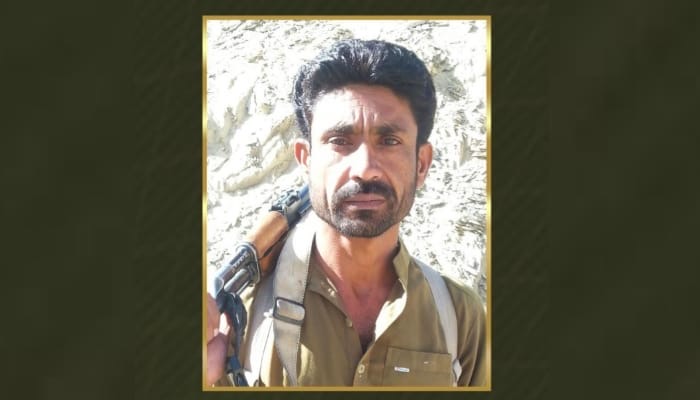

A Ba’athist Veteran in Exile: A Profile of Salah al-Mokhtar

A Ba’athist Veteran in Exile: A Profile of Salah al-Mokhtar

Introduction

After the Anglo-American invasion that toppled the regime of the former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein and his Arab Ba’ath Socialist Party, thousands of junior and senior members of the party fled the country. From their exile in Syria, Jordan, Egypt, Yemen and elsewhere, some of them played a noticeable role in opposing the post-Ba’ath political process in Iraq and supporting their comrades in the insurgency. One of the most prominent figures among these is Salah al-Mokhtar, a former state journalist and ambassador to India who has arisen to be one of the key leaders of the Ba’ath party from exile in Yemen.

Between Divergent Wings of the Party

Salah Abdul Qadir Muhammad al-Mokhtar was born in Baghdad in 1944. He was raised in a neighborhood that was a Ba’ath stronghold in western Baghdad. After the brief nine month long reign of the Ba’ath party in Iraq following the February 1963 coup d’état that overthrew General Abdel Karim Qasim, the party underwent a severe crackdown by the post-coup authorities. That tension resulted in the first split in the Iraqi Ba’ath with al-Mokhtar then choosing to be in the party’s left wing. When the right wing of the organization led by the late Iraqi President Ahmad Hassan al-Baker and his deputy Saddam Hussein seized power in the second Ba’athist coup in July 1968 that ousted the Nasserists who ruled Iraq in the interim period, al-Mokhtar made his way back into the ruling faction. [1]

A Loyalist

Over the three and a half decade long reign of the Ba’ath regime, al-Mokhtar occupied various journalistic and diplomatic positions. In the 1990s he was the editor-in-Chief of al-Jumhoria, the formal daily newspaper of the Iraqi government. He was also the chairman of the organization of Friendship, Peace and Solidarity, a Ba’ath body responsible for coordinating with the international non-governmental organization community.

According to a biography published on a Ba’athist website, al-Mokhtar holds a Master’s Degree in Politics from Long Island University in New York (Uruknet.info, September 1, 2005). He also worked as a media consultant for the Iraqi mission to the United Nations in New York (Albasrah.net, August 17, 2004).

After the Invasion

When Saddam Hussein’s regime was toppled in April 2003, Salah al-Mokhtar was Iraq’s ambassador to the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Following the fall of Baghdad, al-Mokhtar sought refuge under the regime of President Ali Abdullah Saleh, one of Saddam Hussein’s closest regional allies. Post-2003, al-Mokhtar has been relentlessly vouching for the Ba’ath party and the overall Iraqi insurgency in the nascent Iraqi media as well as established Arab outlets. His writings are widely published and are followed closely on sites overtly sympathetic to the Iraqi Ba’ath. He has also been a frequent commentator for political programs on Iraqi and pan-Arab satellite channels.

Al-Mokhtar and the Insurgency

Salah al-Mokhtar was not just an enthusiastic activist who supported the Ba’ath and other insurgent groups. He was a strategic thinker who played a role that only very few Ba’athis could claim. This role appeared not only in the usual Ba’ath web sites. Interestingly, in spite of the usual claims and counter claims between Bathis and Islamists over the role and size of each party in the insurgency, al-Mokhtar’s views were available on Islamist insurgent forums. When al-Mokhtar released an interesting communiqué titled “[An] Open message to the Iraqi resistance” in early 2006, it was introduced and received with a degree of respect by those with staunchly divergent ideological positions to al-Mokhtar.

The communiqué was a plan for the armed groups to deal with what al-Mokhtar calculated as a retreating position of American forces in the Iraqi theater. He claimed to have anticipated an American military withdrawal by the end of 2006 due to the heavy economic and military cost of the war. He called for the different insurgent groups to remain united against any negotiations should the Americans call for them. He also introduced a plan for ruling Iraq that emphasized a central role for the Ba’ath party after the assumed withdrawal of foreign forces (Muslm.net, Jan 17, 2006).

In his self-ascribed capacity as an expert on American foreign policy, al-Mokhtar’s thesis on the relationship between troop drawdown and a renewed place for the Ba’ath was proven inaccurate. In a very personal appeal made by al-Mokhtar across ideological lines, it is worth noting that just talk of his ideas here indicates a rare confluence of the aims of differing insurgent movements in view of the Ba’athist communication with Islamist insurgent groups.

On the other hand, when dealing with other insurgent groups al-Mokhtar approached the issue with comraderie. While being supportive of those insurgents who are essentially competitors, al-Mokhtar has always emphasized the primacy of Ba’athists in the wider insurgency. Islamist insurgents groups have frequently debated that claim (Nasrunminallah.net, March 31, 2007).

In the Post-invasion Ba’ath Party

Salah al-Mokhtar has been a vocal supporter of Izzat al-Douri’s leadership in the Iraqi Ba’ath following the execution of Saddam Hussein. He is perceived as one of al-Douri’s closest associates. Although there has been no indication that the two men have met in person since the invasion, al-Mokhtar has been always a sought after source for information on al-Douri’s well being and activities from his Yemeni sanctuary. Al-Mokhtar has persistently claimed that al-Douri was in good health and leading the resistance inside Iraq (al-Watan, November 13, 2005; al-Arab al-Yawm [Amman], February 14, 2009).

After 2003, the leadership of al-Douri was challenged by Syria-based General Muhammad Younis al-Ahmad, but al-Mokhtar has continually supported al-Douri without fail. As Iraq was heading towards a new stage of the post-Saddam era in the 2010 elections, al-Mokhtar received a very significant sign of appreciation from the supreme leadership. He was the sole addressee in al-Douri’s diatribe on the anniversary of the 1968 Ba’athist coup. From hiding, al-Douri addressed al-Mokhtar in his speech by his kunya (intimate Arabic honorific):

The move was a matter of a major rift and debate between the rival Ba’ath wings. It was received with great skepticism by al-Ahmad’s wing and the other newly emerging, minor Ba’athist entities. It marked the collapse of the fissiparous party’s unification efforts. An enraged spokesman of al-Ahmad’s decried the affair and claimed that al-Douri was already dead:

The transcript of the al-Douri speech published on various Ba’athist websites did not include any specific assignment of a position for al-Mokhtar in the party’s hierarchy. Al-Douri’s acolytes would not have missed an opportunity to attack what looked like inaccurate allegations made by their rivals (Mriraq.com, September 27, 2010).

The biggest blow for al-Ahmad’s faction was not being on the weaker side of an ideological divide but rather when the second man in their group defected and joined al-Douri. On November 27, 2010, General Ghazwan al-Kubeisi announced on al-Jazeera that he abandoned al-Ahmad’s leadership and joined al-Douri (for a profile of General Ghazwan al-Kubeisi see Militant Leadership Monitor, December 2010). Al-Mokhtar was the biggest winner as he had received al-Douri’s endorsement. Though it was not for succession, which al-Mokhtar never himself claimed, al-Mokhtar was assured a senior position within the party.

Under Fire

Salah al-Mokhtar has been always at the center of the debate among the various Ba’athist factions and leaders. Since Izzat al-Douri appears to be off limits in terms of direct criticism, even among his most bitter rivals, their avenue to sow discord was to shed doubts on the reality that he is alive. In this light, al-Mokhtar is a relatively softer target. He has been frequently subject to severe criticism by partisans from al-Ahmad’s group or former Ba’athists.

The accusations against al-Mokhtar range from embezzlement while he was a diplomat under the former regime, to hypocrisy, to being unfaithful when he was ascending the party ladder over the decades. He was accused of tipping off his old comrades from the left-wing Ba’ath when he re-joined the ruling wing in late 1960s (Altawahud.com, May 6, 2011).

At the time of this writing, Salah al-Mokhtar faces a new threat wholly unrelated to Ba’ath rivalries or those in Baghdad that would relish in his downfall. With the ever-growing anti-regime uprising in Yemen, activists from the Yemeni protest movement started to attack al-Mokhtar. They began to hurl taunts at him, accusing him of being an agent for president Saleh’s security service. Al-Mokhtar has reportedly left Yemen to a destination in Europe (Falnaktub.com, May 2, 2011).

The Future

The political consequences of the upheavals across the Arab world are radically altering the landscape the exiled Iraqi Ba’athists have been operating in since 2003. Al-Mokhtar labelled the so-called Arab Spring a Western conspiracy aimed at dividing Arabs. Affected personally by the Yemeni uprising that gravely shook the stability of his host, President Ali Abdullah Saleh, al-Mokhtar has been very critical of the popular movements in the Middle East. He has also been troubled by the revolutions aimed at other passé, radical Arab regimes in Libya and Syria. He has even launched a severe criticism against Qatar and al-Jazeera, of which he was a repeat commentator on the latter. He has accused the Gulf emirate and its wide-reaching satellite channel of serving an American-Zionist conspiracy. He called for the Qatari public to be aware of the perils associated with the policies of Amir Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani, whose recent actions al-Mokhtar described as criminal adventurism. [2]

The results of the political mobility in the wider Middle East will have significant effects on the future of the Iraqi Ba’ath. The situations in Syria and Yemen are of particular note in this regard. New governments with less interest in the regional issues in Damascus would deprive al-Ahmad’s wing of its sanctuary and sponsorship. This sea change will also very likely put al-Douri’s organization in an unpredictable geopolitical equation.

The demise of President Saleh’s rule in Sana’a, which may only be a matter of time, would result in Iraqi Ba’athists in Yemen facing an uncertain future. Al-Mokhtar might be a prolific writer and active commentator but he has yet to demonstrate that he has the diplomatic skills or contacts to secure new alliances for his exiled party. This will not be an easy task for a man whose key skill set consists of justifying radical stances and moulding them in ideological guidelines. Nonetheless there may yet be a glimmer of hope for al-Mokhtar’s Ba’ath. It was reported recently that Saudi Arabia offered military support and sanctuary for the al-Douri-led Ba’ath. (Shatnews.com, June 6). [3]

The real test for the Ba’ath and its future still lay within Iraq’s troubled borders. The party has not seemed to be relying on any popular uprising to achieve its aims. Its strategy is still to depend on military actions as a means to topple the government led by Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki. Unrepentant Ba’athists still seek to resurrect the ancien regime, a highly improbable prospect after eight years. Salah al-Mokhtar had previously tried to make that utterly remote idea appealing to the other insurgent groups by promising that the Ba’ath party will establish a multi-party political system if it was to return back to power. It is unlikely that such a strategy will succeed if Baghdad and Washington renegotiate the U.S.-Iraq Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) to extend the military presence of some American troops, which are scheduled to pull out completely by December 31, 2011. But even a SOFA extension will not halt the Ba’ath from being an active insurgent group.

If no new SOFA agreement is reached and there was to be a total withdrawal, the future of the Ba’ath would decisively hinge on the very fluid regional circumstances that exist today, including the immense Iranian and Saudi influence that now exists in Iraq.

Notes

1. The split extended to the wider pan-Arab organization of the party after the leadership of the Syrian Ba’ath took a left leaning line in 1966. In Iraq, the conflict between right and the left of the Ba’ath deepened and did not stop until the right wing led by Ahmad Hassan al-Baker and Saddam Hussein seized power in the July 1968 coup. The left wing was subsequently banned and repressed. Its leading members fled to Syria where they lived under the rule and support of the late president Hafez al-Assad. It now forms one of the smaller factions of the Iraqi Ba’ath.

2. See: Almogahd69ahlamontad.forumarabia.com, Accessed: April 24, 2011.

3. It is very important here to note that King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia was humiliated when his call for Iraqi politicians to meet in his country to end the seven month long impasse over the formation of new government in 2010 was ignored. The Iraqi factions chose to meet in Erbil instead after the Shia parties, especially the followers of Moqtada al-Sadr, lifted their veto on the Nuri al-Maliki due to what was believed to be heavy Iranian pressure (Alhawra.com, October 31, 2010; al-Madina, November 12, 2010).